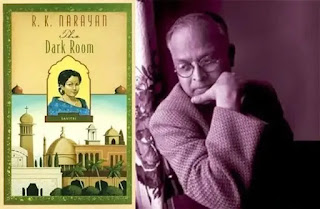

The Dark Room Summary

The Dark Room, Narayan’s third novel, was published in 1938. Critics do not rate it very high. Thus, A.N. Kaul regards it as insignificant and one of Narayan’s failures, and S. Iyengar regards its end as “Cynical Conclusion.”

The Dark Room is a moving tale of a tormented wife. Ramani, the office secretary of Engladia Insurance Company, is very domineering and cynical in his ways, and hence governs his home according to his own sweet will. As he is always irritable, the atmosphere of his house is generally gloomy and his wife, children and servants always remain in a state of terror. His wife Savitri is a true symbol of traditional Indian womanhood. She is very beautiful and deeply devoted to her husband. Ramani, however, does not respond to her sentiments even with ordinary warmth. Though they have been married for fifteen years, his wife has received nothing from her husband except rebukes and abuses. Even his children get more of his rebukes than of his fatherly love.

All goes well, till there arrives at the scene a beautiful lady, Shanta Bai, who has deserted her husband and joined Engladia Insurance Company. Ramani succumbs to her beauty and coquettish ways. This upsets the peace of his domestic life, till seeing no way of correcting her arrogant and erring husband, Savitri revolts against him and in despair leaves the house to commit suicide.

She goes to the river and throws herself into it. The timely arrival of Mari, the blacksmith and burglar, who, while crossing the river on his way to his village, sees her body floating on the river and at once rescues her and saves her life. Persuaded by Man’s wife Ponni, she goes to their village and embarks upon an independent living of her own by working in a temple. The feeling of home sickness and a tormenting anxiety for her children, however, soon make her restless. She realises the futility of her attempt at escape from her bonds with the temporal world and returns home. (Raizada)

Such is this simple novel dealing with the sorry fate of Indian womanhood. It suggests no solutions to the problem, still it clearly brings out Narayan’s concern for the Savitris of our country. Its plot is more coherent and well-knit than that of the earlier novels, the characterisation is excellent, and there is a skilful blending of humour and pathos. Narayan has not preached any sermons but has vividly and realistically presented a slice of life as he saw it. Despite the view of critics, one feels on reading it that it is quite a successful nov and deserves much greater attention than has been usually awarded to it.